CULTURE – CHEWA

The first inhabitants of Malawi were the “Bathwa” (Late Stone Age 10,000 BC-1800AD), who were also known as the Akafula or the “Mwandiwonera Pati?” (meaning from how far have you seen me?).

These people were hunter-gatherers hence the name “Kafula” meaning those who dig for food and roots, or those who spit when speaking because of their clicking language (Bathwa).

Being pigmy-like people: short sized with strong African features upon an encounter, the first question an Akafula would ask was generally: Mwandiwonera pati? translated to, “from how far have you seen me?“.

Being pigmy-like people: short sized with strong African features upon an encounter, the first question an Akafula would ask was generally: Mwandiwonera pati? translated to, “from how far have you seen me?“.

If your reply was ‘I’ve only just seen you‘, there was a high chance you’d get attacked and killed as they found it offensive to not be seen due to their height.

However a sensible answer would always be “I saw you from afar” as they perceived the answer to project they were tall enough to be noticed from a distance.

The Akafula lived in forest and woodland environments and moved seasonally following availability of water and migration of animals. They slept in rock shelters, caves or thickets and did not practice agriculture.

Men were usually involved in hunting animals and women were involved in gathering fruits, berries, nuts and roots.

Akafula as Artists

The Akafula painted in majority of the areas the inhabited.

Figure 1: one of the rock art site in Dedza district (mphuzi rock)

Using red pigments of various hues, the Akafula depicted enigmatic symbols such as circles, stars, grids and animal shapes. Other symbols depicted weather patterns and also the animals they hunted.

The Akafula encounter with the first Bantu (Iron Age-150 AD)

The first Bantus are believed to have migrated from Katanga province in present day DRC. This brought conflict between these two groups, which later resulted in the Akafula being outsmarted and killed, however some Akafula fled out of Malawi to the regions of DRC.

The Banda Clan and their Leadership (1900-1375)

The Banda were one of the two dominant Chewa clans and among them were groups such as Mbewe, Nkhoma, and Chisale.

These groups of the Banda clan were connected by descent and marriage ties through a matrilineal system. They were united by communal rituals such as hunting, puberty (initiation) rites, rain calling ceremonies and the secret society of Nyau which acted as a link to their ancestral spirits.

Their main occupations were agriculture and iron smelting. Among the Banda clan were spirit wives who have been referred to as Mwali earlier on. These resided in shrines and they were political and spiritual leaders of the shrines. They were responsible for calling rain on behalf of the people and presided over initiation rites. If a spirit wife died, they would choose another one.

Makewana (community fortune teller)

The office of Makewana is not hereditary, her election is not based upon membership it is a certain clan but rather on her demonstration of an ecstatic visionary gift which must become apparent to the community during her childhood. Makewana lives alone in her hut, apart from the village. She is not married. An ebony stick and a necklace with a large circular shell mark her special status.

The Coming in of the Phiri Clan ( 1200-1400)

The Phiri clan originated from Luba in DRC and their king was known as Kalonga. The Phiri clan was more stratified and established a centralised government at Manthimba, thus the central Malawi in Salima district.

Soon the Phiri became rulers over the Banda because of their superior technology such as justice system and the development of trade. Many banda traditions were preserved and used by the new rulers to boost their political hegemony including rain shrines, Nyau society and the initiation ceremonies.

It is the descendants of these two groups that form the present day Chewa.

Decline of the Maravi Kingdom (1500-1700)

Subordinate chiefs grew stronger than the Kalonga (supreme leader) through trade, as a result this led to the breaking down of the kingdom into smaller chiefdoms and Kalonga was reduced to nothing as, these subordinate chiefs grew stronger and stronger.

Such kingdoms were Lundu (found in southern part of Malawi in the Chikwawa District.), Undi (now referred to as Kalonga Gawa Undi in Zambia), Kaphwiti (northern part of Malawi in Nkhatabay district) and Kanyenda (central part of Malawi in Nkhotakota district).

Later the Swahili, Yao and Ngoni invaders finished what was remaining of the Maravi kingdom.

The myth of Kaphirinthiwa. (The myth for the creation of life)

There was no rain; the earth was dry and sterile. Then God-Namalenga (the creator) gathered the clouds together and God-Mphambe (the lightning) made the fire flare in the sky and thunder roar in the mountains. Rain fell and the wind swept the Kaphirinthiwa Mountain leaving a clean, soft surface.

God-chauta (the big bow) cast his rain bow across the sky, touching the clouds. In the pouring rain, came the first humans, with their tools and all the animals.

Man carried a hoe and an axe to cultivate the land, and the woman with a pestle and mortar to prepare food for the family. In the soft surface of Kaphirinthiwa mountain, the footprints of the humans and the animals were preserved and can still be seen today on Kaphirinthiwa mountain.

Names of God in Chewa Society

Different names are used for God in Chewa society, each name expressing a special attribute.

Chiuta / Chauta: Literally meaning “the big bow”.

This is a symbol of how God shows his concern for his people by giving them rain.

Chisumphi: this name is mainly used in reference to rain sacrifices.

It has the special meaning of God listens to man’s prayers.

Mphambe: Literally meaning thunder and lightning and these are the signs of his power.

Leza: Literally meaning to nurse and to be gentle and kind. So this simply means God the sustainer of people.

Chanjiri or Nanjiri: This means the strong one.

Namalenga or Mlengi: Meaning God the creator of the world and people.

The verb ” Kulenga” means to create or to make.

N’theradi: God the mighty one or the true one.

Matsakamula: The one who has the power to bring down rain or the one responsible for making the rain fall.

Mulungu: this literally means to put together rightly and God is seen as a God of order and perfection.

There is also a strong belief among the Chewa society on the role of ancestors. Ancestral spirits strictly refer to lineal senior kin and senior relatives who are seen as protectors of the society. These are commonly referred to as “Mizimu ya Makolo” or ancestral spirits. These are also guardians of the societies’ customs.

These ancestral spirits communicate with the living through dreams of which only diviners can give an authoritative interpretation, but not directly through visions or voices.

Sacrifices to the Ancestral Spirits

Offerings are made normally only to the Mzimu (spirit) of one’s own lineage. The quality and quantity of the offering is in proportion to the dignity of the deceased.

To an adult, one may offer a goat but to a child one might offer a chicken. This can be interpreted as a gesture to show the spirits that they are still remembered; hence they should continue protecting the village.

If sacrifices are not offered to the spirits, misfortunes may fall on the society such as poor harvests, strange diseases, deaths, disasters such as floods. Therefore spirits have to be remembered all the time.

Such sacrifices can be offered once a year especially towards the end of the year. Offerings are made at a special place in the bush called a “Kachisi” or a “Shrine”.

Death in Chewa society

When a Chewa person has died, the relatives of the deceased would first inform the chief in the village. In his turn, the chief would send young men to inform the chiefs of the surrounding villages. In the past these young men would carry with them a black chicken (note: black as a symbol of grief) to each of the chiefs as a token of their grief.

However, today this ritual is only carried out when a chief dies. In the past, from then until after the burial no-one within the village would be allowed to eat meat, as meat is portrayed as a dish for feast festival, and as a result would be interpreted as an insult to the deceased’s spirit.

However, today this ritual is only carried out when a chief dies. In the past, from then until after the burial no-one within the village would be allowed to eat meat, as meat is portrayed as a dish for feast festival, and as a result would be interpreted as an insult to the deceased’s spirit.

Nevertheless, in modern day the no meat rule has stopped, and people do eat meat at funerals. Majority of deceased people get buried within the village cemetery.

Soon after burial, people especially the relatives of the deceased may perform a ritual, this is known as ” First shaving” whereby all the family members of the deceased person have their hair shaved as a symbol of grief and also to chase away the spirit of the deceased person for fear of being haunted by it.

There is a belief that the spirit of the deceased person may haunt the family members and may enter into their bodies through the head, hence the reason for shaving off the hair.After a period of six-months, the second and last shaving takes place and this marks the end of the mourning period.

Religious Significance of the Chewa Secret Society (Gule Wamkulu-Nyau)

The Nyau dance has a special religious significance namely; it is the symbolic representation of the invisible spirit world. The Chewa also painted rocks as a way of teaching their children the symbols of the Gule Wankulu.

The Chewa rock art is different from that of the Akafula because the Chewa used white substance in painting while the Akafula used blood of animals as well as fruit colours

Figure 2: Chewa rock art depicting characters of Gule Wankulu

Chewa Traditional Dances

Birth and puberty

Chisamba chantheko (last born)

Chisamba cha mimba (pregnancy)

Mptapasa

Marriage

Kaulesi

Kanganye

Beer party

Makuleya

Hunting

Ulenje

Rejoicing

Olanje

M’ganda

Mphalasa

Henga

Ntopale

Chimtala

Chim’bwiza

Moya

Mjiri

Moya

Dambelo

Masafu

Jachigon’go

Khunju

Mchomanga

Chiltelera

Sesenya

Gaula

Chieftainship

Kazukuta

Nguluti

Chiponda

Funeral

Tunduwale

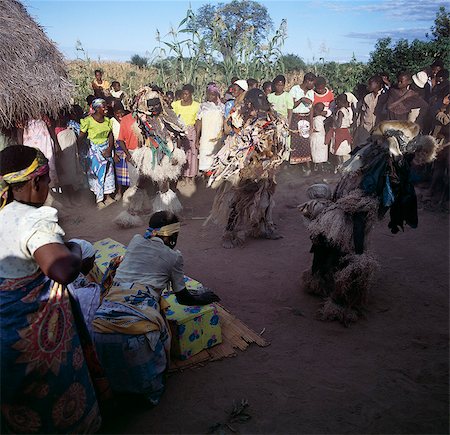

Gule Wankulu (The great dance or big dance)

Gule Wankulu also known as Nyau, was officially proclaimed on the 25th November, 2005 by the UNESCO as a masterpiece of the oral and intangible heritage of humanity.

The Gule Wankulu masquerade ranks highly among the institutions that serve as custodians of oral tradition and culture in Chewa society.

These can be seen through a great variety of human characters that play various roles and social functions. Gule Wankulu teaches awareness reminding of social values, safeguarding of unity and harmony within the society, respect to vulnerable people and the sanctity of life, humility in front of Gule Wankulu.

It involves everyone through songs and dances, each one individualised according to his talents.

Characteristics of the Nyau People

They leave the village and live at the grave yard or “Dambwe” situated at the graveyard where normally people never go.

They speak a secret language.

They have to observe taboos on sexual relations because they have to remain “calm” (ritual calm) by reason of their close contact with the spirits of the dead.

They curse freely which is normal life to them when they are at the “Dambwe”

They fight, chase and assault women if they are not respectful when passing each other.

They go about practically naked, are dirty and paint themselves with mud and ashes.

They shout obscenities at one another without respect for the difference of generation and social status.

They sometimes steal chickens from the village.

Some Gule Wankulu Characters

Namalocha: comes out during the funeral of the chief only and this mask stresses the message of prohibition and sexual taboos.

Gandali: stresses the “mwambo” (teachings and values) of ancestors.

Chimbano: (big pincher), grabber or thief. Carries knives, spears and clubs. Performs at female initiation ceremonies and mostly reminds people the importance of moral behaviour in marriage by remaining faithful and avoiding jealousy and conflict.

Dzimwe: this character dances the night vigil of funeral and commemoration rites.

Chinkhombe: means “shell”, often used as a spoon in Chewa domestic life. It is also used as an ornament and it symbolises feminity.

Mayino: dances at funeral commemorations. This mask emphasises the weak role of the husband in a matrilineal society and the difficulties in taking up residence with his wife’s family in her village.

Chadzunda: (head of the spirit world as well as ancestors) this mask is the most ancient and prominent of all masks of Gule Wankulu. Chadzunda embodies the “mwambo” (Customs, law and order) the code of morality and the power of fertility.

Maria: this mask was invented when the early missionaries came into conflict with the Gule Wamkulu as they were looking at it as being evil hence telling the Chewa to stop this dance. But the Chewa refused and retaliated by inventing this mask called Maria to symbolise “Mary” mother of Jesus.

The Diviner

For the Chewa, illnesses and death are rarely due to natural causes but to spirits or enemies. It is the duty of the diviner to indicate who caused or “sent” illnesses or death.

The diviner holds a very important position in Chewa society because he is the only one who can interpret by means of his “lots” (Maula) the will of the spirits of the dead.

These ancestral spirits are believed to send misfortunes in order to punish or warn their living descendants. The interpretation of the diviner is essential to ascertain what the “Mzimu” (spirits) want to convey. The diviner can also tell whether an enemy or a witch caused the misfortune and how his influence can be counteracted.

All diviners have one thing in common, thus they ask their clients to supply all necessary information and to give details of, for example illness and the relationship in the family and the village. The diviner is also interested to know if there were any disputes, whether the sick person has enemies, whether they are jealousies, whether any relative has recently died.

This background information helps the diviner to diagnose the disease and give proper medication.

The diviner is also a sole authoritative interpreter of dreams and premonitions which people believe the spirits of the deceased send to warn them of impending danger or to convey some other message.

The following are samples of actual dreams and their interpretation:

A person who dreamt that he received what he asked for from someone was told that this was the promise of good fortune.

A person who dreamt that he was attacked by an animal without being hurt was told that this was a good omen.

A person, who dreamt that someone in the village had died, was told that something untoward was going to happen.

A person who dreamt that he was chased by a snake was warned that somebody wanted to kill him.

The Medicine Man (Singa’nga)

The term singa’nga is used for a person who uses, prescribes and administers herbal medicines to cure diseases and to protect property. The medicine used to protect property is called “M’tsiliko”

Malawian Witch Doctor

Examples of M’tsiliko (Medicines for Protection)

To protect a house: this is done to prevent “mfiti” (witches) and thieves from entering the house. People ask the medicine man to protect their houses. Usually he comes at midnight and buries some of his “Mankhwala” (medicine) in all the corners of the house. The composition of such medicine is basically a mixture of charcoal, castor-oil and a powder made from the roots of the “Mwabvi tree” (Erythrophleum guineense) and “Kankombwe” (pistia stratiotes)

To protect the body: a person who suspects a neighbour of harbouring evil intentions against him and is afraid that he might be poisoned will ask the sing’anga for medicine to protect him. This medicine is usually done through the rubbing of the medicine into the skin (incision)

To protect grain stores: in order to prevent thefts, a horn (Nyanga) containing Medicine is placed at the bottom of the grain store. The medicine man will go sometimes to the grave to dig up the skull of a small child (preferably the skull of the child of the sister of the owner of the grain store) this skull is placed at the bottom of the grain store and covered with an earthen ware pot. This type of medicine is also believed to increase the maize in the grain store and it is normally referred to as “Mfumba”

To protect the fields: to protect against thieves, spells and wild animals, a “Chambu” (type of medicine) is used. This “mankhwala” (medicine) consists of roots dipped in castor-oil and covered with ashes.

The owner of the field makes holes at each corner of the field and at the place where a path leads back to the village. In each hole the medicine man puts some medicine and covers it with soil except for the hole near the entrance of the field which he covers with a small earthen ware pot.

He shows the owner how to lift this pot and put it back again. The owner may only enter the garden through this “entrance” and after lifting the pot. If anyone dares to enter the field in another way or without lifting the pot, they would become lame or possibly even die.

To protect a cattle kraal: to protect cattle against thieves, wild beats and disease, people put medicine in holes around the kraal and on both sides of the entrance. The teeth of a hyena are believed to curl up while a thief is said to see only a pool of water and no kraal.

To protect a wife: to prevent their wives from committing adultery some husbands make their wives drink “Chambu” (medicine) obtained from the medicine man. Anyone committing adultery with such a woman would contract a disease which only that particular medicine man can cure.

For girls and women: to make herself loved, a girl wears a “Chisomo” round her neck, a sachet containing a part of the root of “a mwiyo” or of the “Cheseo”. She may also hide such a piece of root in her hair. This is also called “Mankhwala a chikondi” (love medicine).

For hunting: for protection, hunters wear “Mphinjiri” on their arms and rub their weapons with leaves of the “Msolo” (pseudolachonostylis maprouneifolia) to ensure success, they tie a piece of root of a “Mpetu” (Boscia sp) on their spears or insert the heart of the “Sunthe” mouse in the hollow shaft in the arrow.

According to the people, this mouse is very slow moving, so when wounded the game cannot slows down to the speed of the slow moving mouse. To attract game, hunters take the heart of the first animal they have killed and pierce it with the root of “Msolo” (Pseudolachonostylis manprouneifolia) or a “Mdima” (Royna lucida).

The heart is roasted and eaten. The name of the medicine is called “Chikoka” (that which draws near). The Chikoka medicine ensures that game approached by the hunter will not be afraid instead it draws closer to him.

To have a good harvest: some people say that from the moment they plant the seeds they should abstain from washing their hair or body. They may not have any sexual relations with their wives until after the maize is harvested.

To make oneself invisible: the tail of a hyena makes a thief invisible. He has to press the tail firmly with his hand and with this the thief may vanish into thin air.

To win a judicial process: some people buy a “mphinjiri” from the medicine man and keep it in their pockets pressing it lightly. This will ensure that the adversary is confused and unable to put his case clearly enough to win it.

To keep money safe: people boil a mixture of the dung of “a fufuta” (sort of rat) the yellow flowers of the “Katupe woyala” (lasiosiphon kraussianus) and a coin and encircle their money with it.