MALAWI HISTORY

Did you know?

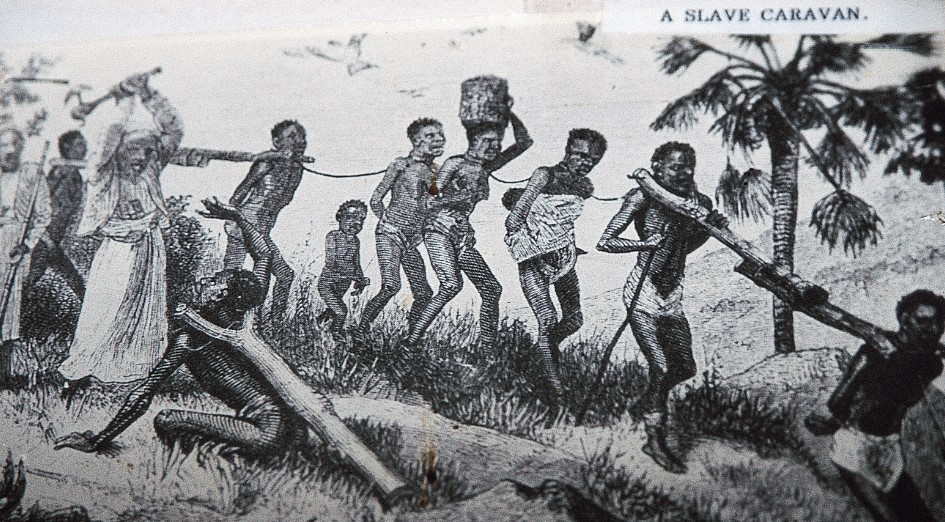

During Slave trade, slaves caught in Malawi, were shipped across Lake Malawi and made to walk for three to four months carrying heavy ivory and goods, if they grew ill or expressed tiredness they were beheaded?

The first organised settlements are thought to have taken place in about 8,000 BC, when the Akafula, part Bushman, part Bantu, who lived from hunting and fishing, moved in from the north. Some 9,000 years later, the first Bantu groups began to appear from the north and west.

They were agriculturists and iron-smelters and more warlike than the Akafula. At first the two co-existed peacefully, but in the 16th Century the Akafula were overrun and decimated by the Amaravi from Katanga.

The conquerors established their rule over the lake country and over areas of what are today Zambia and Mozambique. The Maravi Empire lasted for over two centuries.

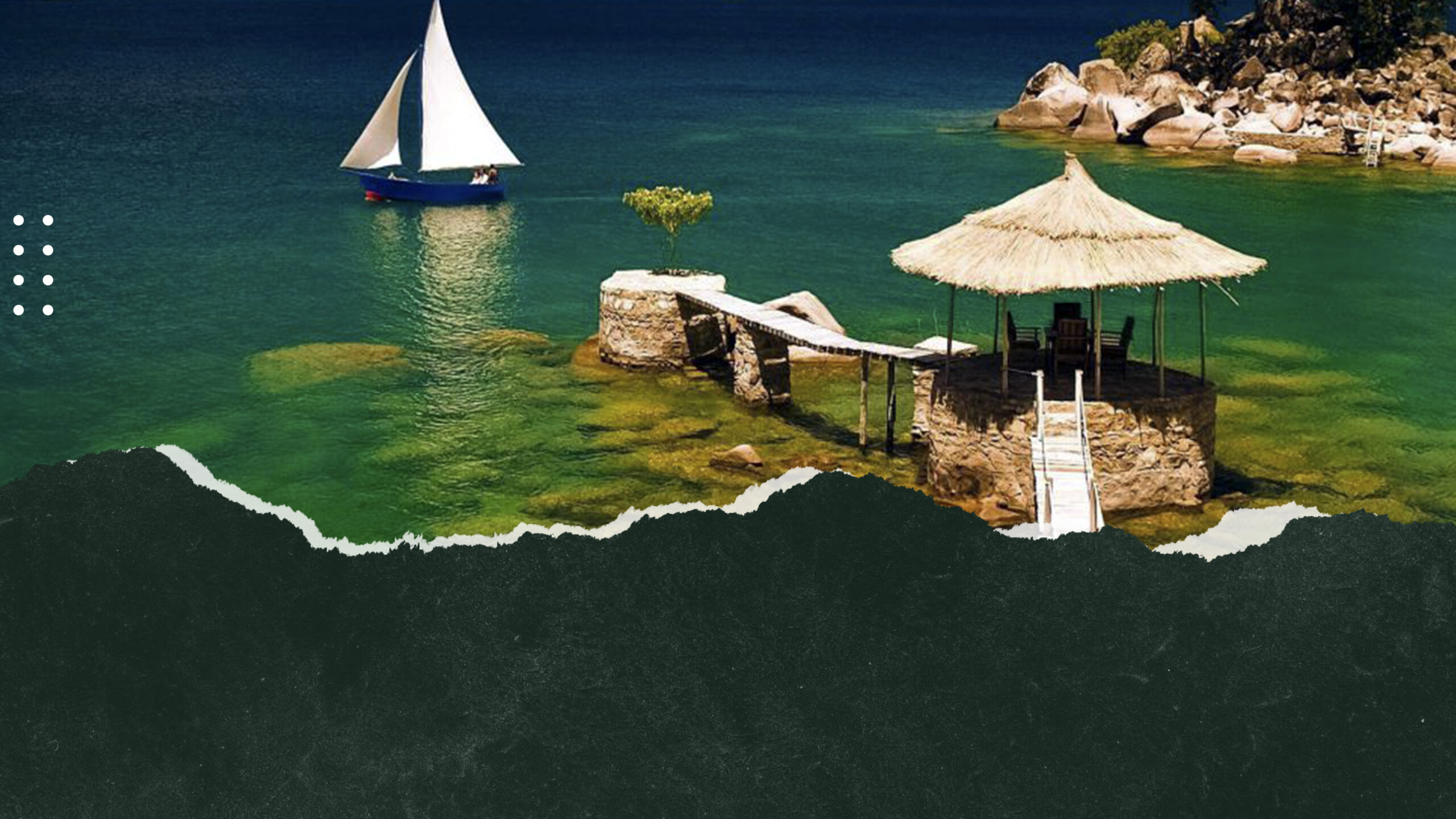

In 1859 David Livingstone, the British missionary explorer, first reached Lake Nyasa, as Lake Malawi was then called, the Maravi Empire had collapsed under a series of invasions.

The Yao themselves driven by Arab traders from their territory in northern Mozambique had entered from the north and west inspiring terror by their raids and mass destruction of Amaravi settlements. In the 1840s Arab slave-traders had begun to enter the lake country from Zanzibar and, often assisted by Yao chiefs, captured and enslaved whole communities.

This period of violence, fear and atrocity continued until the Arab Sultan Mlozi’s defeat at Mpata, near Karonga by the British in 1895.

A British protectorate was declared over the Shire country in 1889 and extended over the hinterland and adjoining Lake Nyasa in 1891. In 1907 the country was named the Nyasaland Protectorate. In 1953, the territories of Nyasaland, Southern Rhodesia and Northern Rhodesia were incorporated into a Federation.

In 1960, a new constitution was introduced, which provided for the direct election of Africans to the Legislative Council. Dr. Banda became the first Prime Minister in 1963.

The Federation was subsequently dissolved and independence was formally granted on July 6, 1964. The country was renamed Malawi which is a modern derivation of Maravi which means “land of the fire”. Malawi became a member of the United Nations in 1964 and joined the Commonwealth in 1966.

In 1970 Parliament declared Dr. Banda Life President of the Republic. The Malawi Congress Party was then the only political party in the country and Malawi continued as a one-party state until 1994.In March 1992, a Pastoral Letter issued by Malawi’s Catholic bishops decried the oppressive policies of the dictatorial Malawi Congress Party regime under Dr. Banda.

This initiated a movement for political change. Major donors added pressure in May 1992 by suspending non-humanitarian assistance to Malawi. Reluctantly, the Malawi Congress Party Government gave in to demands for a referendum to elicit people’s opinion on the continuation of a one-party state.

Two new parties, the United Democratic Front (UDF) and the Alliance for Democracy (AFORD), gained prominence. In a referendum, held on June 14, 1993, more than 60 percent of Malawians voted to change to a multi-system of governance.

Subsequent to the Referendum, Malawians went to the polls on May 17, 1994 to elect a new Parliament and a President by universal adult suffrage. The UDF President, Bakili Muluzi became Malawi’s first democratically elected President for a five-year term. Muluzi was re-elected in 1999.

Although he tried to stand for a third time through a Bill known as the Third Term Bill, he was forced to concede to defeat and the party paved the way for Bingu Wa Mutharika to run on the UDF ticket. Wa Mutharika won the 2004 race beating four other contenders.

The current Constitution, adopted in 1995, provides for a Presidential system of government and guarantees fundamental human rights including freedom of speech and association.

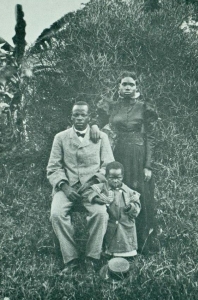

Reverend John Chilembwe – Hero for Independence

Reverend John Chilembwe was born in 1871 he was an orthodox Baptist educator and an early figure in resistance to colonialism in Nyasaland.

Reverend John Chilembwe was born in 1871 he was an orthodox Baptist educator and an early figure in resistance to colonialism in Nyasaland.

Chilembwe attended the Church of Scotland mission from around 1890. In 1892 he entered the domestic staff of Joseph Booth, a Baptist missionary.

Booth was critical of the Scottish Presbyterian missions in Nyasaland, where Chilembwe had been educated, and he established the Zambezi Industrial Mission. Importantly Booth’s teaching focused on equality, a radical idea in colonial Africa.

In 1897 Chilembwe travelled with Booth to Lynchburg, Virginia, where he attended Virginia Theological College, a small African-American seminary. Here Chilembwe was exposed to the works of John Brown, Booker T. Washington and other abolitionists.

The Beginning of the Uprise

After 1900, Europe began to introduce changes to colonial rule in an effort to increase revenues from the colonies. These changes included taking land from African people and giving it to the growing number of Europeans in the colonies.

The other changes were the introduction of taxes like the hut tax and poll tax that forced Africans to work for European settlers. Africans were forced to work for Europeans in order to pay these taxes. This was because the new taxes had to be paid in cash and not as cattle or crops as was the practice before.

Exploitation of African labourers by European employers added to the growing resentment among the local people.

In 1900 he returned to Nyasaland as an ordained Baptist minister. Working with the American National Baptist Convention, he founded the Providence Industrial Mission, which developed into seven schools, which by 1912 had 1000 pupils and 800 adult students. He tried to instil the values of hard-work, self-respect and self-help in his community.

A Resistance movements began to rise in Africa. In colonies with a growing number of settlers, the demand for more land and labour increased tensions between colonial authorities and the white communities that had settled in the colonies.

African Land Distribution Amongst Colonials

More land was taken from African people and given to Europeans for settlement. In response to these developments, some chiefs organised rebellions against colonial authorities.

In 1913 a famine caused hardship, and people from neighbouring Mozambique moved to Nyasaland. Chilembwe was upset by the way his parishioners and the refugees were exploited by plantation owners. Workers were denied wages, and beaten.

William Jervis Livingstone, a plantation owner, burned down rural churches and schools established by Chilembwe. Chilembwe also was affected by the conscription of local men to fight for Britain in Tanganyika (Tanzania) against the Germans in World War I, for no immediately foreseeable benefit to Africans.

He complained of racism and exploitation. On the 23rd of January 1915, Chilembwe staged an uprising: he and 200 followers attacked local plantations that they considered to be oppressing African workers. Chilembwe’s plan involved the killing of all male Europeans. They killed three white plantation staff, including William Livingstone, whom they beheaded in front of his wife and small daughter.

Several African workers were also killed, but they did not harm any women or children on orders of Chilembwe. When the uprising failed to gain local support, Chilembwe tried to flee to Mozambique; however he was killed by officials on February 3rd, 1915.

Failed Chilembwe Plot

Although Chilembwe had sent letters to neighbouring Zomba and Ntcheu encouraging them to organise coordinated uprisings, his word did not arrive on time. When his letters finally arrived on the 25th of January, the authorities had already known of the plot and the hastily coordinated uprisings had failed to accomplish.

The colonial officials also killed a number of Chilembwe’s followers. Chief among the victims of these reprisals were the 175 Africans listed on the uprising’s “War Roll” and the 1,160 names on the list of Baptised Believers. Though unsuccessful, the uprising prompted the government to reconsider the land and labour practices in Nyasaland.

These were major causes of the uprising. They had been introduced mainly to exploit the colonies by extracting more labour from them and squeezing more productivity from the workers to lower the cost to the colony.

At the same time taxation on black people was increased. The uprising had the effect of raising the awareness of black people to colonial rule and encouraged them to stand up for their rights and demand an end to colonial rule.

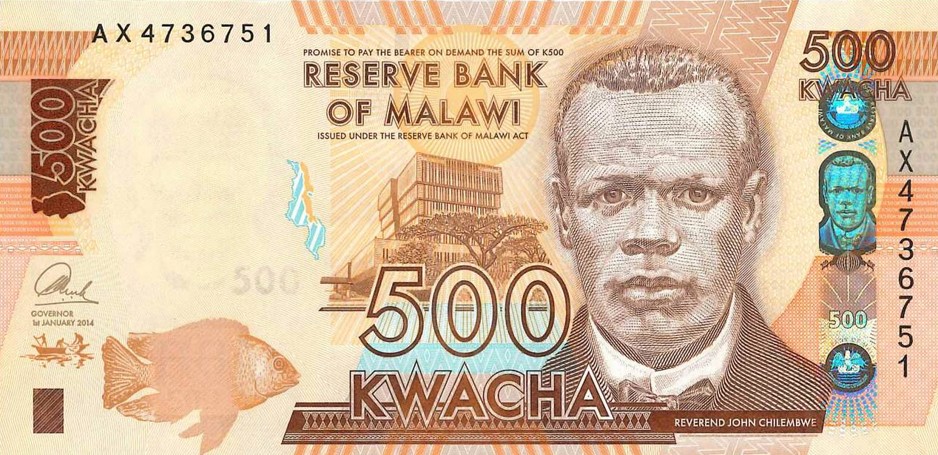

Today Chilembwe’s likeness may be seen on the obverse of all Malawian kwacha notes and he is celebrated as a hero for independence, annually on the 15th of January in Malawi.