CULTURE -TONGA

The Tonga in Tongaland

Physical location

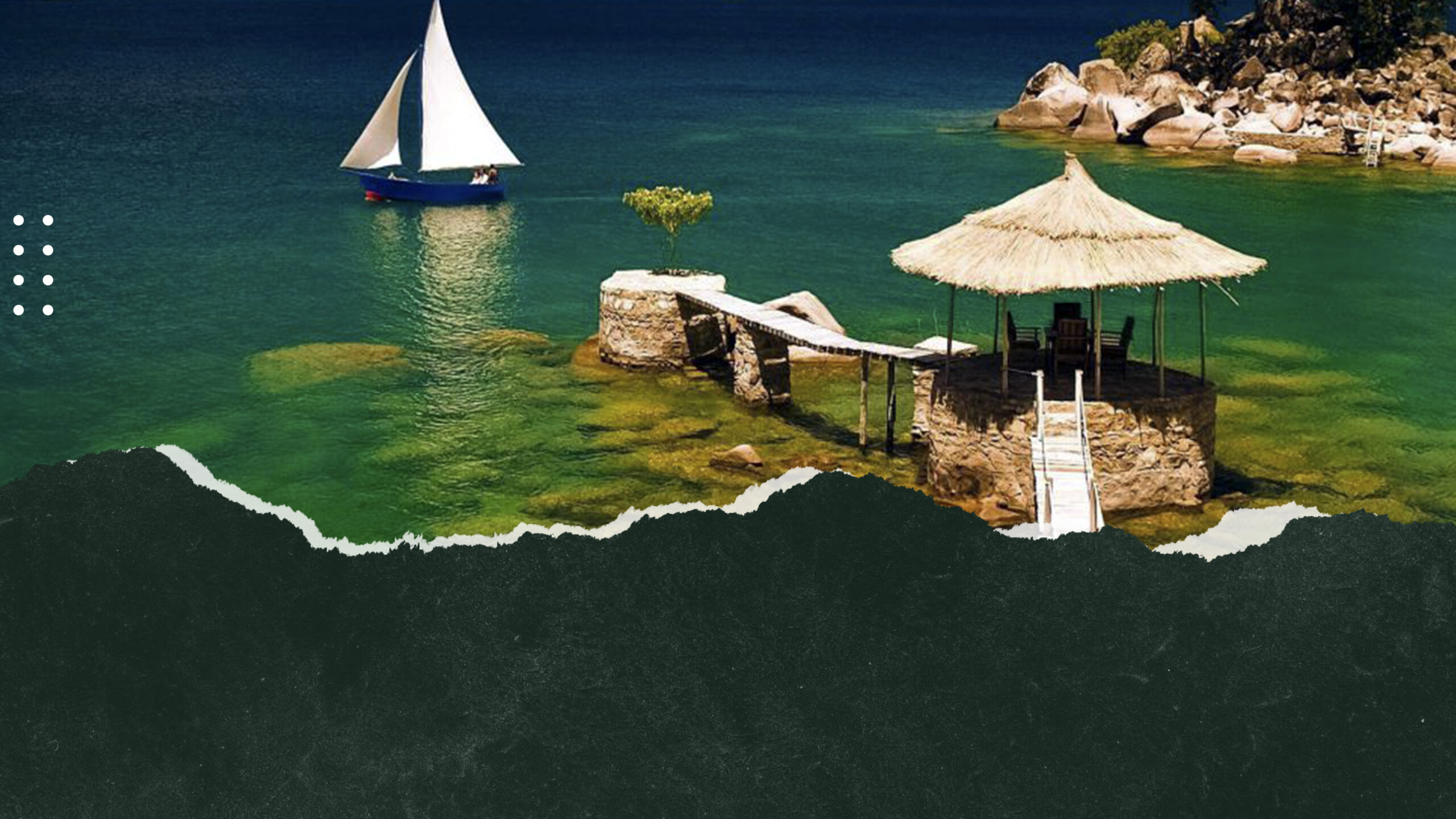

The Tongaland is bordered by the Vipya range of mountains to the west, extending north and south of the Luwenda River as well as the Kawandama mountain ranges in the south. The land is broken by high ridges of the foothills of Vipya. There are few large rivers and numerous perennial streams. There is a strip of flat land along the lake in the shape of a wedge. Furthermore, its thin end is a few kilometres south of Nkhata-Bay and it gradually broadens southwards. The neighbouring ethnic groups are; the patrilineal, cattle keeping Siska, who lived in another pocket to the north, however across the lake, are the inhabitants of the Likoma and Chizumulu Islands.

Tongaland was also known administratively in the colonial days as West Nyasa district border, later as Chintheche and today as Nkhata–Bay district, bordered on Tumbukaland to the North and West, and Chewaland (matrilineal society who are basically agriculturalists) to the South. Its southern neighbour is Nkhotakota where Swahili Arab influences were strong during the nineteenth century.

Historical background

There are several migration traditions attributed to the coming of the Tonga. For instance, some people claim they came via the watershed between Lake Tanganyika and Lake Malawi. Others claim that they came from present day Zambia. Whilst other traditions claim that they came from the East and crossed the lake via rafts, This is because the Tonga were among some of the ethnic groups that came into Nyasaland (present day Malawi) between 17th and 19th centuries. Other ethnic groups included the Yao, Sena, Ngoni, Lomwe, Nkhonde and the Tumbuka. All groups are believed to have migrated into Malawi due to the penetration of Ivory trading groups from north eastern shores of Lake Nyasa (present day called Lake Malawi) and the ethnic movements in the northern part of Malawi. It also believed that the Tonga came from the same place as the Chewa and Tumbuka. People who believe in the latter conclusion possibly see some similarities in “Chichewa” and “Tumbuka” names found in Chitonga (Tonga language) such as Phiri, Banda and Mwale.

In addition to that such similarities can also be seen in some languages. For instance, the English word tobacco is referred to as fodya in Chichewa, foja in Chitumbuka as well as Chitonga.

The Tonga people spread out beyond the limits now defined as Tongaland for various reasons such as;

- Internal and external disturbance

- Land shortages

- A desire to return to old sites or other localities of later choice

Later on these clusters came to amalgamation for at least four different groups: the Nyaliwanga Tonga, whose home area is Timbiri around Mpamba and Chakwina, and who may be the oldest inhabitants of Tongaland. The Nyaliwanga Tonga were also the people who fought the Ngoni at Uliwonele, a Tonga hill in Nkhatabay. The second group was Kabunduli with his followers the ‘Phiri’ (Phiri also means hill in Chichewa) another group who are found mainly in the hill region westwards, around the upper reaches of the Luweya River; the Kapunda Banda who settled by the lakeshore, south of Luweya, and who may have been Chewa off shoot entering their present habitat from the south; and the Mankhambira and Kang’oma who are said to have come across the lake with guns. This process of amalgamation was increased by the external forces among others; including the raids from the Ngoni under Mberwa in the 1850s. Hence, they retired into stockades (large fortified villages) called Malinga rather than living in small tattered villages. The four stockades (Malinga), known from tradition and from travellers’ accounts are;

- The linga of Mankhambira and Kang’oma by Chintheche River

- Malenga Mzoma’s linga by Bandawe

- Chavula’s in Matete valley just south of Bandawe

- Chinyentha linga, just south of the Luweya

The Tonga Social Structure

It is an egalitarian society made up of equals; a chief is first among equals. One point to be noted about the Tonga society is that every individual has two common family names. One is derived from the father and represents his ‘chiwongo’ whilst ‘fuko’ (clan) represents the mothers side of the family. In cases of inheritance or succession, it is the latter or mother’s title that is generally adopted. In the pre colonial past where a cluster of chiefs resided in a particular locality, say south of the Luweya river among the Kapunda Banda, seniority among the chiefs was arrived by observing in whose Mphara or public meeting place the initiation ceremony rites for girls or the nkhole was held. Gradually these rites became distributed among all the chiefs and thus the only measure by which seniority was judged ceased to exist, thus adding to the egalitarian nature of Tonga societies.

In addition to that, the small groups attached in various ways to the group village headman (fumu) may claim a direct or primary link with his /her, children or through membership of the headman’s matrilineage. The category can further be divided into patrilocal residents whose ties with the village are patrilateral throughout, that is, the headman’s children and his son’s children, and those villagers whose link with the village however do not follow either line. This interaction has an influence on moral attitudes to their close neighbours.

Tonga's Kinship and Locality

A Tonga village constitutes of around 20-50 houses based on kinship or genealogy. Furthermore, people’s distribution is highly determined by the geographical position. For instance, it is densely populated along the lakeshore and low population along in higher ground areas. Getting to the villages can be reached via steep winding paths up which both visitors and residents must negotiate to reach their settled community at the top, however not to forget that these paths are used by the Tonga women daily with their water containers balanced on their heads from a well or from a running stream below the hill. Kabunduli and Timbiri areas are typical of such features. The staple food of the Tonga is cassava. The cultivation of cassava requires comparatively hard labour and can be done entirely by women. Cassava is normally served as a thick porridge (sima/kondole) together with a side dish relish (dende). The favourite relish consists of, chicken meat, or fish and this is the kind of relish which every host strives to offer his/her visitors. The Tonga rarely raise cattle, goats, and sheep- except the few that can be seen. There are few cash crops of minor importance such as rice, bananas, maize, tobacco, millet, coffee and tea. Most of the millet, coffee and tea are cultivated in the hills.

In addition to that the Tonga call all the settlements muzi (plural mizi). The expression for hamlet leader and village headman shows the same flexibility. For instance, fumu (plural mafumu) can refer to either office. The word fumu or its abstract counter ufumu (headmanship/chieftainship) is sometimes used as synonymous with munangwa (freeman), as opposed to kapolo (slave). Furthermore, the Tonga kinship pattern puts stress on the bond between men and women within the same patrilineage. They distinguish two primary categories of kinsmen; kuchinthurumi (on the man’s side), and kuchinthukazi (on the woman’s side) call their daughter-in-law mkumwana. Tonga wives live virilocally, unlike the matrilineal Chewa where the husband lives uxorilocally. However, among the Tonga uxorilocality is very rare. The words mkumwana (daughter-in-law) and mkosano (son-in-law) also have the same implications as mlanda (orphan) and kaporo (slave).

Tonga Marriage Customs

Marriage is the most important factor integrating otherwise independent groups of kinsmen. Marriage serves not only the end of ordered procreation but has emotional, domestic, economic and political functions. The Tonga political system is basically a system of overlapping networks of kin groups and kin interests. Furthermore, the transactions which precede a formal marriage should fulfil several stages such as;

- Chijula mlomo (mouth opener) – the initial stage of opening the mouth cost MK200.00 or more. This money is a proof or public negotiations and it establishes a formal marital relationship.

- Chikole (betrothal payment) – which varies from MK7000.00 or more. This does not establish any legal rights. It is handed directly through the girls grandmother or female cousin.

- Chiziya pamuzi (home coming) – involves a payment of MK1000.00 or more.

- Chimanga matumbo (tying the intestines), a payment that is given to the mother of the girl as a token for giving her daughter, and involves a payment of MK200.00 or more

- Chisinkha pamuzi (protecting home) –is the idea of appeasement or security of the home that ensures the girls ancestors approve and are happy that the granddaughter is getting marriage. The payment varies accordingly.

- Chilowola/chimalo (bride wealth) – is the legal payment in a formal marriage. The general rule is that there should be a go-between (thenga), who comes from the village where the suitor is resident and always sent by the attorney (nkhoswe). In recent years the amount of chilowola has gone up from MK1000.00 to MK 5000.00 at times even more.

To the Tonga marriages create bonds which extend beyond village or other geographical boundaries, they create a common focus for individuals or groups who may be spread over a wide area. Marriage rituals are powerful. For example, a wedding is an occasion which attracts the inhabitants within the neighbourhood of the village. Polygamy is also practiced by other Tonga clans.

Tonga Beliefs

The Tonga believe in a Supreme Being, hence God is portrayed as the creator, the source of all life/death, and giver of rain. In addition to that God is denoted with names such as;

- Chiuta

- Leza

- Mlengi

- Mulungu

- Chata

These names indicate that God is a supreme spirit. In addition to that they also indicate the ultimate source of moral good, hence God’s moral attributes. Apart from God, the Tonga also believe in supernatural powers (i.e. ancestral spirits) which are believed to be the custodians of morality. They also have a mediating role such as receiving petitions from the living and direct it to God. Therefore, the ancestors become the intercessors. In other terms there is veneration among the Tonga.

Furthermore, the Tonga also believe in mystical powers i.e. spirits that can posses people, witchcraft as well as sorcery. However, names like Mwatimara or Tamara denote the existence of witchcraft. In addition to that, the Tonga also believe that a witch incarnates or turns into a peculiar creature (ndondocha) to travel in disguise at night or even during the day.

Tonga Dances

- Chioda (it is predominantly performed by women)

- Kanchoma (It is performed by both sexes)

- Mangolongondo (It is predominantly performed by men)

- Visekese (Predominatly performed by women)

- Chilimika (Performed by both sexes)

- Mtangala (Performed by girls and women)

- Ndelitha/kordioni (Performed by both men and women)

- Maskawe (Usually performed by both men and women possessed by the spirits)

- Malipenga (Predominantly performed by men)

However, some of the forgotten dances or dances which have died a natural death include;

- Gulutu.

- Mchoma and

- Gule wakawole.

Among these dances, the most popular are the Chioda, Ndelitha and Malipenga. They are performed on special occasions.

a. Chioda dance

The Chioda dance is a ceremonial dance performed by women on a night before the wedding ceremony.

b. Ndelitha Dance

It is performed on the day of a wedding ceremony. It is marks the establishment phase of the marriage as it involves equal participation from both men and women.

c. Malipenga dance

This dance forms the base of the Tonga society. It is organised with a territorial theme. Each dance group is called ‘Boma’. However, the Boma is separated from others by a river. A group of villages may form one Boma. The villages constituting the Boma may for example be the Mankhambira, the Kapunda Banda and the likes. In addition to that the villages constituting a Boma may strongly oppose one another.

Functions of Malipenga

Malipenga has a unifying/ reconciliatory factor. It is also used as a form of initiation. In this regard each Boma has someone in charge usually denoted either as a Queen, King, Captain, or Sergeant major. It is also a source of entertainment, hence performed on weekly basis. They are commonly performed during the dry season as well as during school holidays. Furthermore, it teaches moral code such as honesty, obedience, communal life, cleanliness, friendship as well as reconciliation.

Dressing Code for Malipenga

- White shorts

- White shoes

- White/khaki T-shirts

- Hats with protruding coil of feathers

Note: there is flexibility in dressing these days hence any uniform can be worn.

Furthermore, the drums are modelled in a military style. The gourds (lupale) on the hand are used to dramatise trumpets. On the other hand, the songs often depict historical or political events such as the police under the British colonial rule. Some carry a message of praise to the queen, captain, sergeant or king from where the Boma belongs. Other songs carry moral instructions such as cleanliness, obedience as well as respect for elders.